Electronics was passion, obsession, raison d’etre. In the early sixties I was a ten-year-old kid with a basement laboratory, and my happiness was a function of solder smoke, blinkenlights, clacking relays, and the mystery of radio. As I slogged through school, the only things that mattered were science fairs and gizmology.

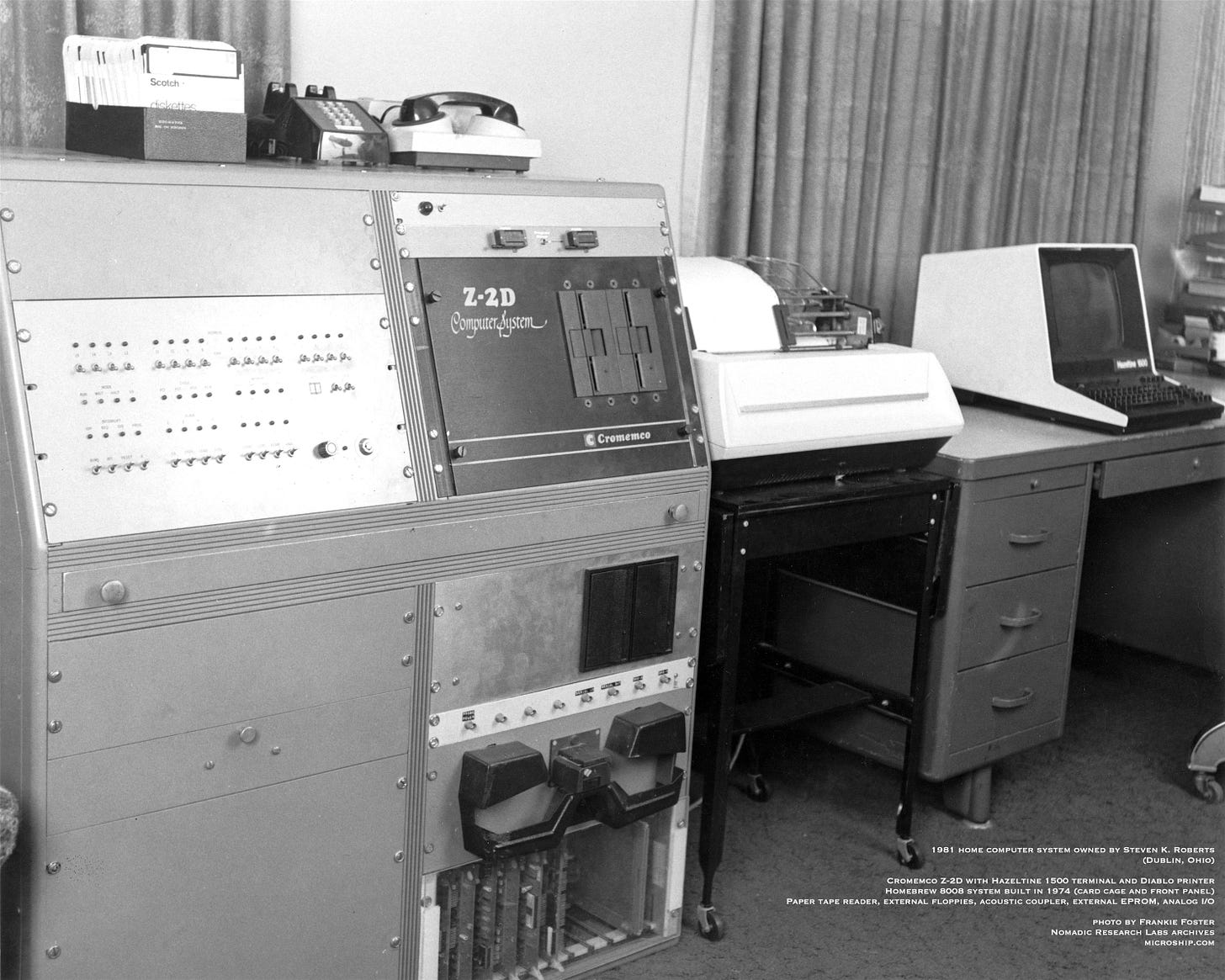

A decade passed. I spent most of 1974 building a homebrew computer while starting a mail-order parts business to support my silicon habit. All this led to a few years of industrial control system design, followed by an engineering textbook.

My twenties were a hand-to-mouth marathon of geeky projects fueled by freelance writing — double-spaced manuscripts submitted “over the transom,” phone tag with editors, dozens of subscriptions, library card catalogs, paper correspondence, and 5-drawer file cabinets stitching it all together. I flew to conferences every few months, armed with article assignments. Writing was license to be a generalist: artificial intelligence, robotics, library science, computational linguistics, LISP, process control, the computer scene… anything fun.

But in 1983, I was chained to my desk like everyone else, pounding away on WordStar, trying to hit keys in the right order so people would send me money. I was just shoving bits around, yet computers were huge, phones were hardwired to the wall, and long-distance charges were horrific (about $350/month). Sharing a project required face-to-face interaction, so collaborations were limited to neighbors unless there was the time to drive or money to fly. Everybody had folders of faxes and nth-generation photocopies, and exotic “online information retrieval” tools were a dollar-a-minute or more.

Yet something was burbling. Time-share computer companies had discovered that individuals were willing to pay for text-based online services, and hobbyists were firing up bulletin-board systems. Suddenly the modem was the most interesting part of a computer, and while it was a complex wild-west scene that imposed daunting filters, we were seeing a huge cultural shift. Imagine being able to talk to someone in another country for free, without the propagation subtleties and technical complexity of ham radio. Online communities coalesced around every subject, active around the clock.

While all this was unfolding, there was pressure to make computers portable… and thanks to Kyocera, a “notebook computer” known as the Radio Shack Model 100 burst onto the scene in April 1983. For a little over $1K, one could carry around a 4-pound machine with 32K of storage, built-in text editor, 24 hours of battery life, and 300-baud modem. Imagine… I could fly to a conference, write a story in the hotel room, fire it off to an editor, then sign on CompuServe and hobnob into the wee hours on the CB simulator. Oh, the implications!

The stage was set. It was obvious: if my product was words, and words have no mass, then it no longer mattered where my body was.

Let’s jump off and see where this takes us. The 7-minute video above is the inhalation to a decade of geek adventure… and in our next issue, the idea will snap into focus.