The First Digital Nomad

Introduction - 17,000 miles aboard a geeky recumbent bicycle (1983-1991)

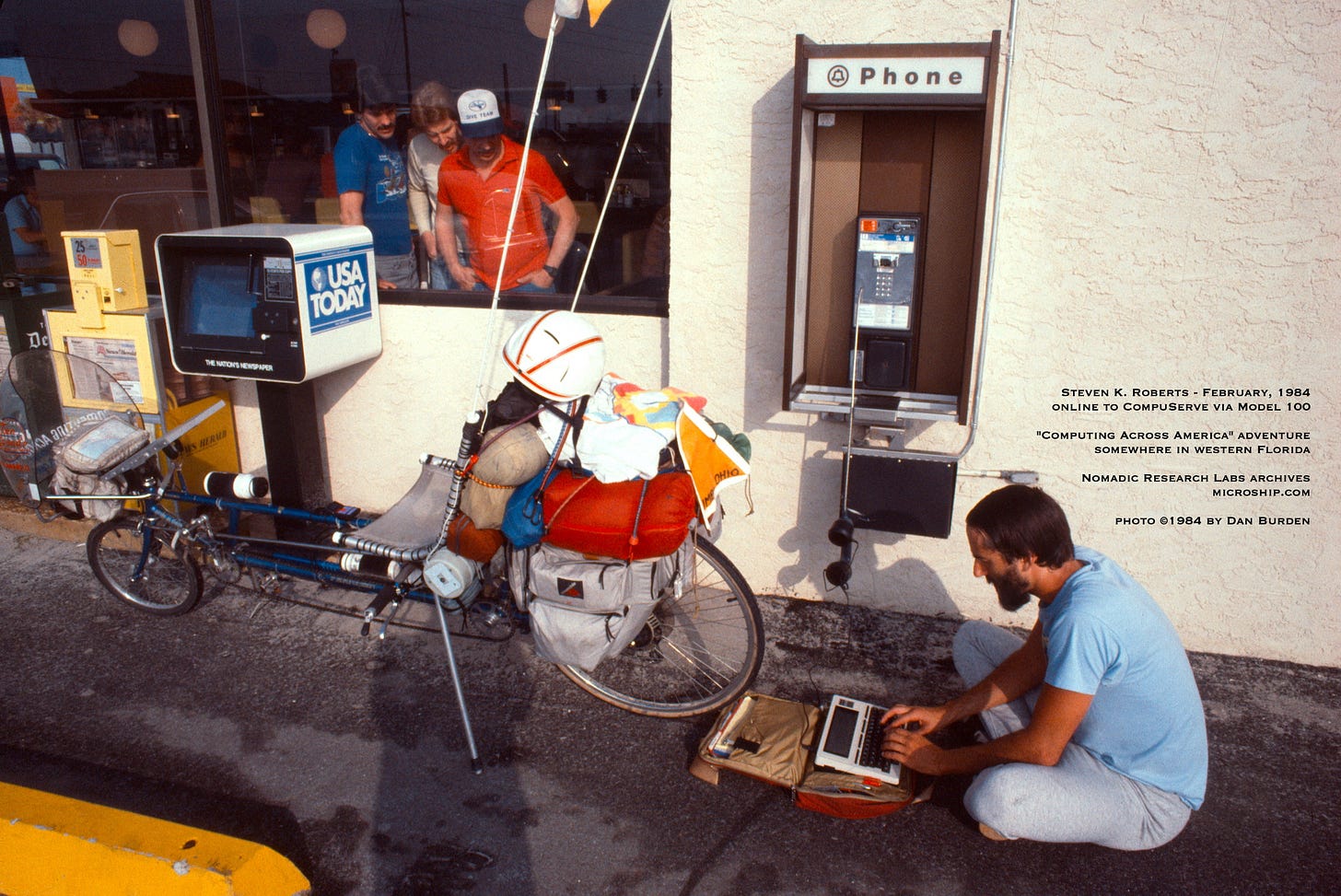

This tale begins at a time of primitive computer and communications technologies. Cellular phones did not exist, going online cost a few dollars an hour for cumbersome text-only services, and people were debating whether one could work at home instead of going to the office. We were chained to our desks by wired phones, fax machines, and tons of paper.

I was a 30-year-old freelance writer with a mortgage in Ohio suburbia… but the more I thought about this, the more absurd it seemed. If my product was words, and words have no mass, then why would it matter where my body was? With the advent of portable computers and networking tools, shouldn’t it be possible to run a business while mobile? A crazy idea began to take shape…

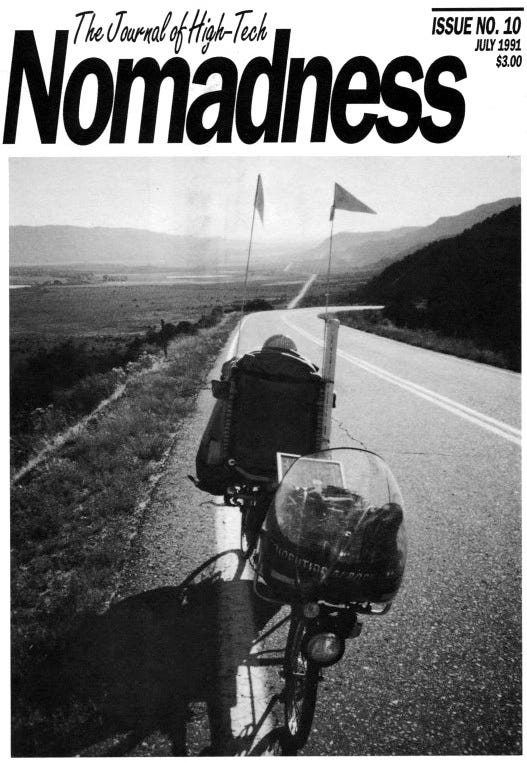

After six months of obsessive preparation, I hit the road in September 1983 on a custom recumbent bicycle with solar-powered laptop, CompuServe account, and a base office. The idea was to use the network to stay in touch with clients and publishers while traveling full time, and as the months passed I refined my tools to render physical location less and less relevant. "Work at home? Work anywhere!" I exuberantly wrote, sensing that I was pedaling on the cusp of major cultural change.

It may have started as a bicycle tour, but what I didn't expect was that the media would be enchanted by nomadic connectivity. The trip was becoming a career, but I fantasized about persistent telemetry, wireless data, substantial data storage, and writing while riding. When the 10,000-mile mark rolled around in 1985, I threw myself into development of the Winnebiko II.

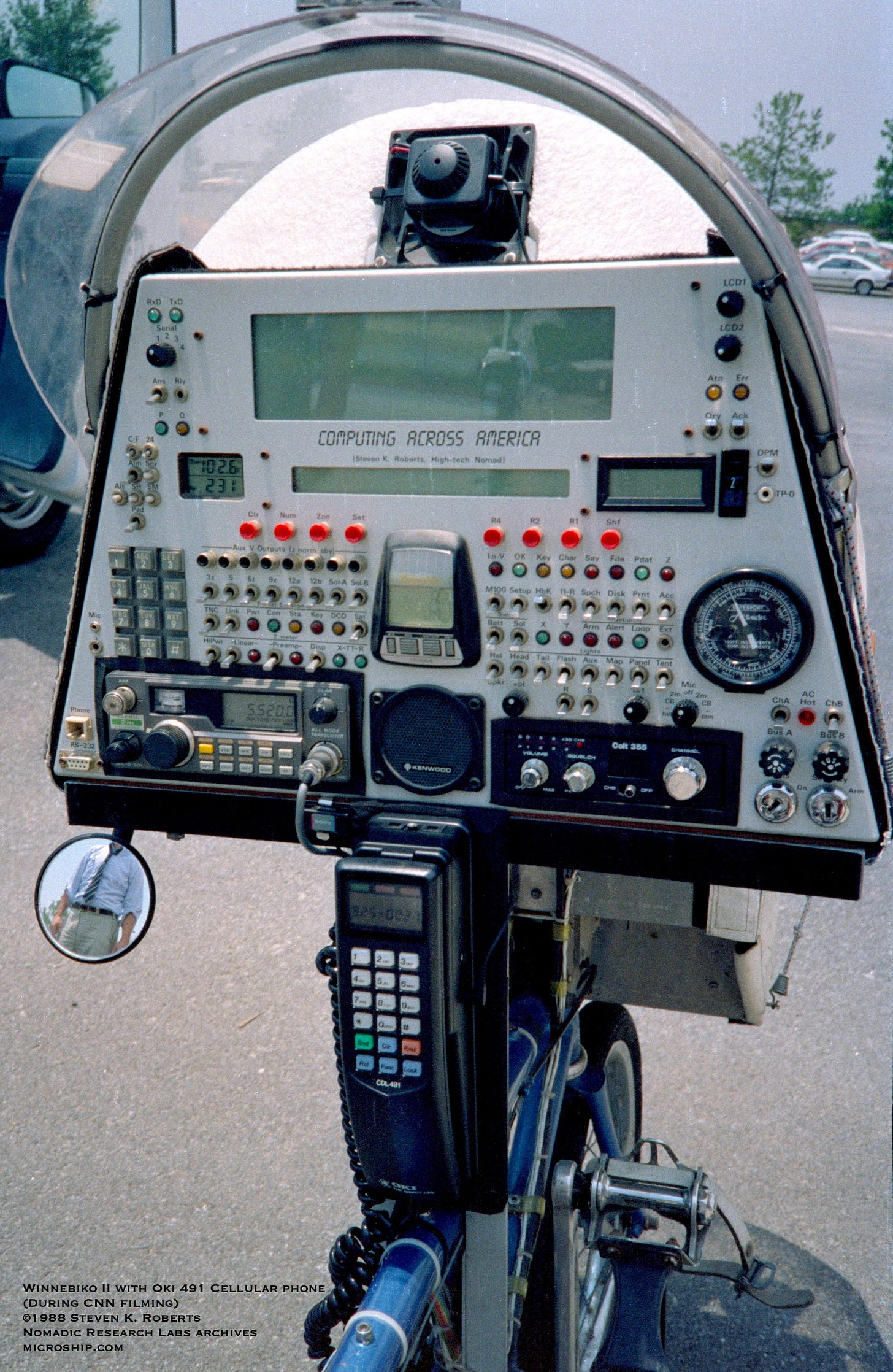

This was an intense year of system design and fabrication, layered atop the original frame. With a binary handlebar keyboard and console computer, I could now work while underway, and a packet radio system even allowed me to wirelessly communicate with hams around the US or beacon my arrival in a new town. With a speech synthesizer and bicycle control processor, the machine could interact with bystanders, and a security system helped me keep an eye on it. 20 watts of solar panels relaxed the power budget, and the console felt like an aircraft cockpit.

I teamed up with a partner named Maggie, and we rode 6,000 miles on both coasts of the US as stories flowed like hot breath. The online world became, literally, our home.

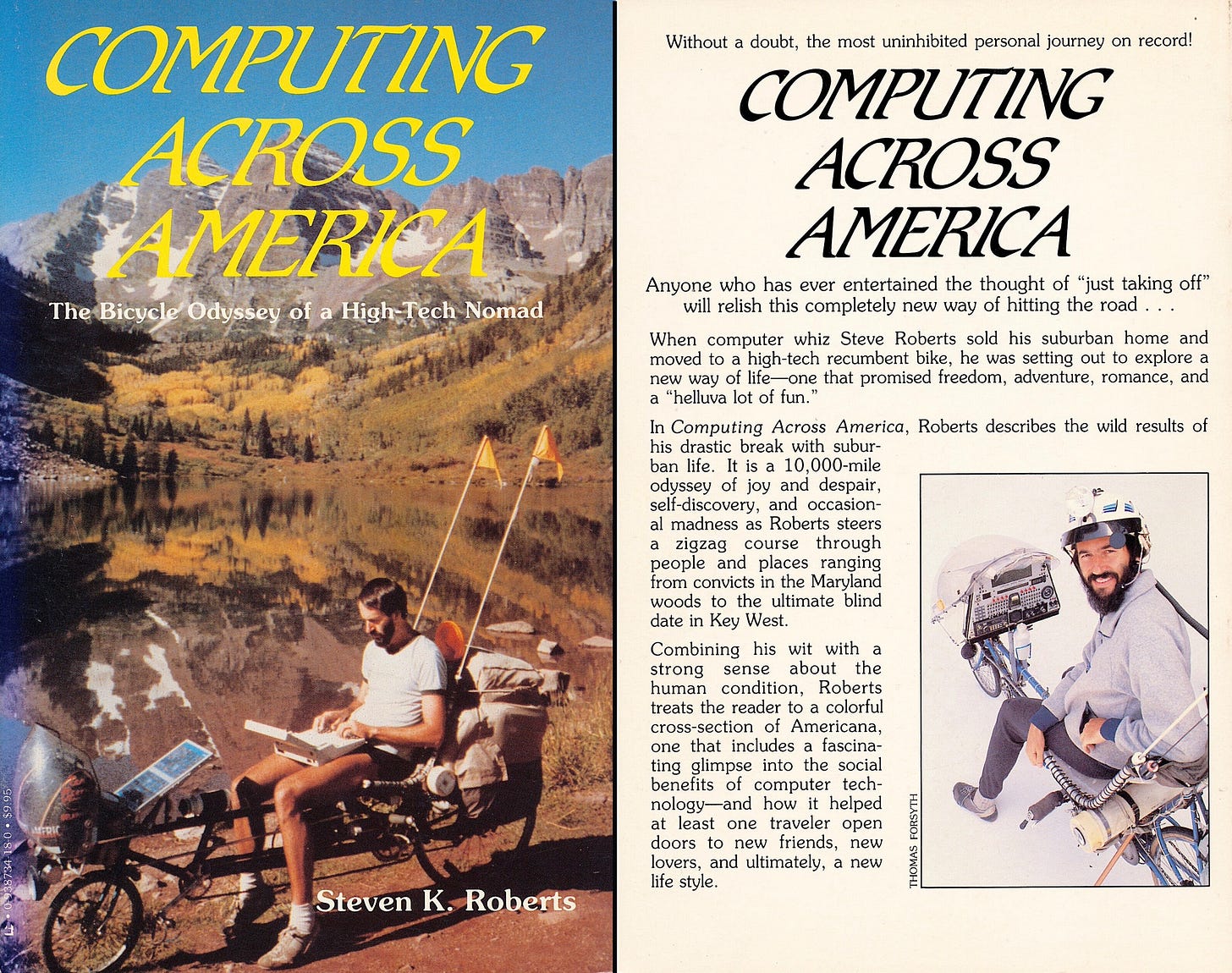

Of course, as an incurable gizmologist, fantasies of the “ultimate bike” still played continuously in my head. We visited new sponsors to pick up geeky treasures, prowled trade shows, and wrote magazine articles about the implications of our technomadic tools. When Computing Across America came out, we converted a 35-foot school bus and went on a year-long book tour — eventually landing in Silicon Valley to build BEHEMOTH — Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine… Only Too Heavy.

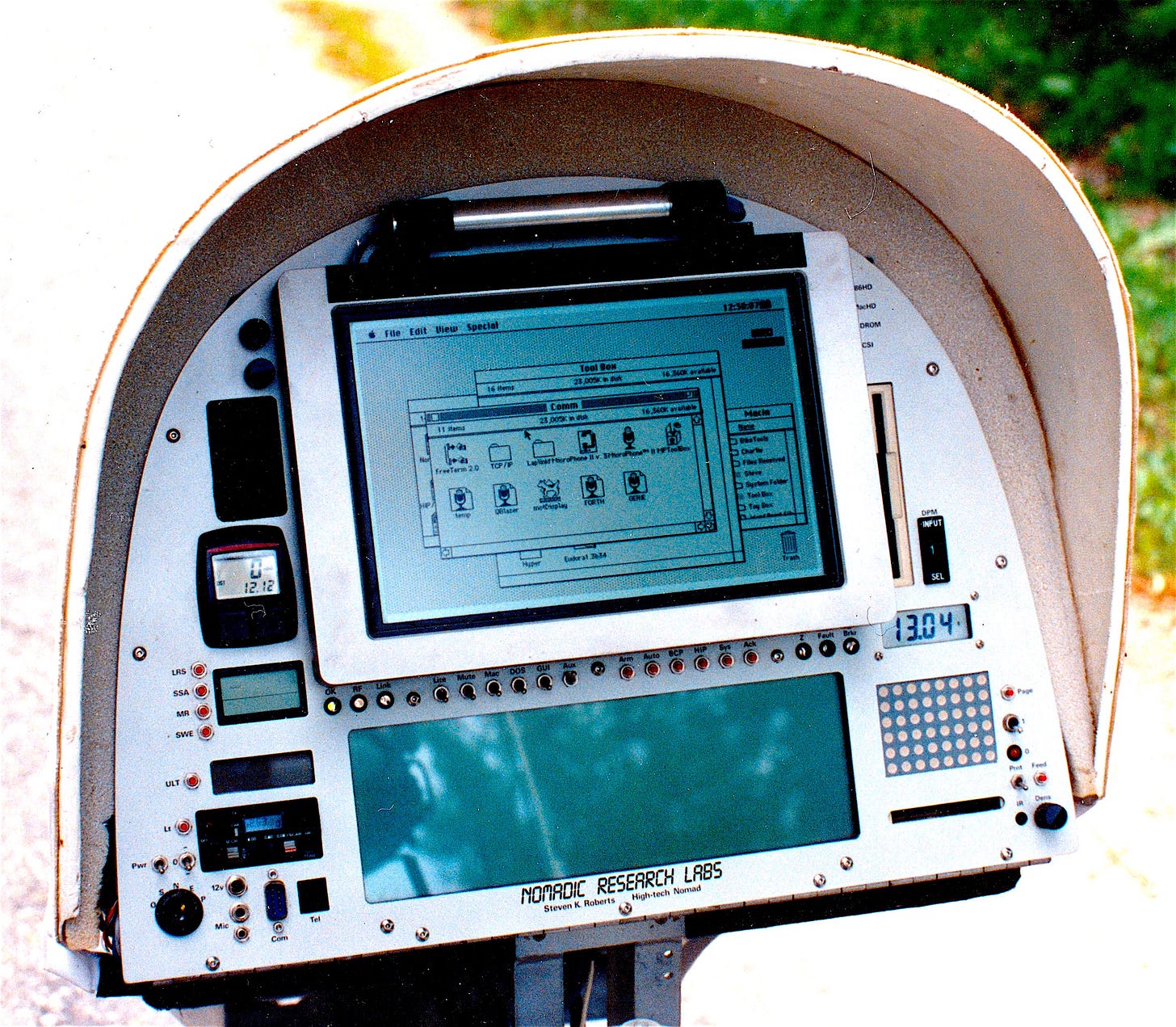

Thus ensued 3.5-years of total immersion… with deep learning curves including fiberglass, sheet-metal fabrication, machining, FORTH software, novel system architectures, harsh-environment packaging, networking, bike tech, power management, embedded systems, audio processing, antenna design, and more. We had about 160 corporate sponsors, along with over 45 volunteers who contributed brilliance and skills. A sort of mini-NASA emerged in lab space donated by Sun Microsystems — a team of geeks driven by the obsession of integrating the best available technology into a networked recumbent bicycle worth an estimated $1.2 million.

This 105-speed machine had satellite email, IP connectivity via cellular, 82 watts of solar panels, console Macintosh and SPARCstation, active helmet cooling, a robust multimode ham radio station, heads-up display, ultrasonic head mouse, crosspoint audio switching, and a trio of bicycle control processors running under a HyperCard front end. It was insanely heavy at 580 pounds (loaded), so had a 7.9-inch ultra-granny along with pneumatically deployed landing gear to allow me to crawl uphill. There was technology to compensate for the weight of the technology… and I learned that if you take an infinite number of very light things and put them together, they become infinitely heavy!

But when I trundled out of the lab in the summer of ‘91, it was delicious.

Road Stories - Then and Now

Forty years later, this all sounds obvious, but when this adventure began in 1983 it was difficult for people to grasp that that once you move to “Dataspace” you can put your body anywhere you like. Physical location matters about as much as one’s alma mater, and interviewers would sometimes offer to swap lifestyles on the spot. “Hang on… you’re doing my job, but you get to travel full time while I sit at a desk under fluorescents? No fair.”

What this meant in practice was that my connection to readers was the most important thing of all. Every day or so, I would upload news from the road, check in with my base office in Ohio, deal with publishers… then go hobnob in the “electronic pub” where I could find my friends or make new ones.

As the years passed, this was distilled into online postings, print publications, and the Computing Across America book… and my mailing list was a treasure. I would post questions while working on projects, and within minutes would receive technical advice from the gurus, hands-on help offers, equipment donations, and invitations to spend the night if I ever pass through. It became normal for me to have close working relationships with people I had never met, and when I fell in love online in 1983 and had “the ultimate blind date,” it was a cover story in the local paper.

Looking back from 40 years down the road, I realize that I was documenting not only a bicycle trip, but a time of cultural upheaval. So many twists have been lost in the vapors of history — and even as we were erasing familiar geographic boundaries, we were creating new ones (“Oh, you’re on Prodigy? I’m afraid we can’t communicate; I am on CompuServe. You’re probably weird anyway...”)

I’ve been talking for years about getting the book out Real Soon Now, upgraded with sequelae, tech details, commentary, and asides. But that is not enough — the original scope was partly defined by a publishing deadline, then dated by a nightmare scenario of delays, and what I now think of as “three bike versions” were really one grand adventure with multiple overarching themes and a continuum of applied mobile gizmology. A comprehensive book about all this would be an expensive full-color beast, with sidebars and appendices… a project of daunting scale.

And that leads us to this moment, right now, here on Substack. I have been realizing lately that this is a much better way to do it, not a serialization, but a publishing model that echoes the on-the-road series from long ago while adding current perspective. I have tons of material from those days — stories, photos, tech info, cultural context, media treasures, digitized video including recent productions, on-the-road audio, and commentary from some amazing people.

The plan is clear: I’ll post a chapter every Wednesday, leaving well-polished narrative untouched while including added framing that would be impossible in print. There will be inline video where appropriate (starting with a 6.5-minute piece called Prehistory of a Technomad, embedded in Chapter Zero).

In addition to email distribution, the permanent archive will have forward/backward links to make it easy for new arrivals to catch up, and I’ll maintain a Table of Contents with short summaries for reference.

Subscribing is free, and no paywalls are planned… I’ll open up voluntary monetizing once it is well underway. At 72, I need to bring this story back to life now, while I still can… and I look forward to sharing the adventure with you via weekly updates.

Cheers from the road!

Steve

I'm looking forward to reading more. Thank you for bringing your story to maybe even more people. ... de N6XDX

I’m so glad that this story is coming back to life! Congrats!