When the virus of restlessness begins to take possession of a wayward man, and the road away from Here seems broad and straight and sweet, the victim must first find in himself a good and sufficient reason for going. This to the practical bum is not difficult.

— John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

It was a summer of madness, of frenzy, of transition. The certainty never wavered — except occasionally in the dead of night when I lay snug in my waterbed and fell into fearful fantasies of the journey: not the usual thrilling ones, but dark ones, tragic ones. Drunken hostile rednecks in roaring pickups would force me off West Virginia mountain roads and I’d lie in the ditch, injured, only to wake in a blue tangle of bicycle and find myself staring numbly into the gaping maw of a 12-gauge…

But such moments were few. They happened on the bad days — down times when the Idea seemed impossible and absurd, when the Unknown seemed too vast, when home and hearth held me in their comforting embrace. They happened when newspapers reported disaster; they happened when well-meaning friends told me of the horrors Out There.

Everybody had advice. I was warned about rednecks, blacks, and maniacs; Texans, Cubans, Cajuns; Hoosiers, hookers, Hispanics; dogs, drunks, and diseases. I was told to carry a gun, mace, machete, flares, and medical supplies. The moments of fear tore at the foundations of my escape fantasy and ruined a few nights’ sleep.

But the rest of the summer was a crash development program — with lists, dedicated staging areas, and a few critical-path management techniques to bring the impossible complexity of this project under control.

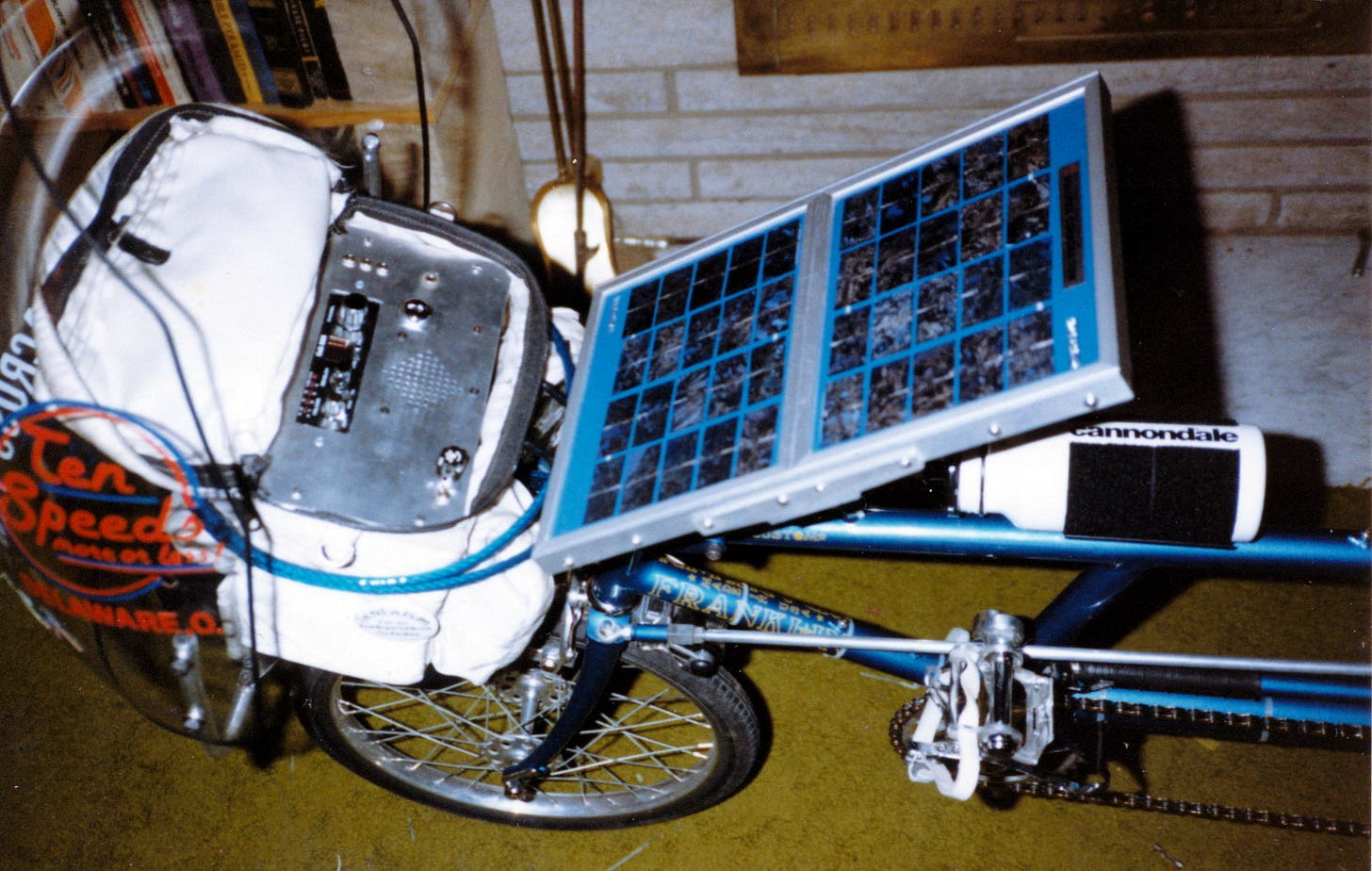

The task was easy enough to define: All I had to do was dismantle an active lifestyle, create a high-tech bicycle, install my home and office on the stern, then pedal the whole affair around the United States while continuing to write for a living.

No problem.

Signs went up immediately, promising free coffee to passers-by if they would step inside and poke through the excess baggage of my life. Everything had a price, from ancient typewriter erasers to the house itself, and I even started accepting Visa and MasterCard in this world-class garage sale. My possessions dwindled.

A neighbor bought the TV and I made a deposit on a Sierra Designs Domicile tent. Three wide-eyed hobbyists went berserk over my prices on electronic parts and drove away with a carload, leaving me with enough cash for a Svea camping stove, North Face sleeping bag, and a whole bag of random accessories. Holes developed all over the house as liquidation progressed, and the “trip room” grew more cluttered.

Classified ads appeared in the local papers: “Prime Dublin land, only $1.73 per square foot. Buy now and receive FREE three-bedroom house!” The response was not encouraging, and within a month I turned the problem over to a realtor.

Literature poured in from all over: brochures on solar panels, brakes, camping gear, radio equipment, tools, and more. I began thinking of old friends in terms of layovers, and I spent hours gazing at maps. Someone pointed out that I should start getting my cardiovascular system in shape, so I signed up for a twice-weekly aerobics class at the local athletic club. (My unofficial term was erotics, of course, since I was the only male in a class of twenty-four.)

The Idea became an Obsession; my life was focused on the odyssey as if it were a curtainless Ft. Lauderdale hotel on a Spring Break Saturday night. But as the exuberance of April dulled to a hazy Columbus summer, I was forced to consider the other realities of this madcap undertaking: Bad knees. Publishing deals. Setting a departure date before the winter of ‘83. Establishing and staffing a home office. And, as always, the lack of money.

“What are you going do about Lumbotech?” asked my friend Frank Feczko one afternoon. Frank was a mid-40’s Hungarian Catholic realtor from Pittsburgh who had become something of my life consultant, and as we sat at my kitchen table he was doing his best to make me look at the journey realistically.

“Well, I’ll pay ’em, of course.” With a casual wave I dismissed the overdue $8,000 cognovit promissory note to a local computer firm — a grim reminder of one of my less successful enterprises.

“With what?” He sat across from me, figuring on a paper napkin. “You need four grand a month to pull this caper. You think you got problems now?“

I studied the upside-down figures.”Wait a minute, Frank, you still have the house payment in there.”

“Of course! You still have the house.”

“Yeah, but it’s for sale.”

Frank rolled his eyes. “Oh, God! You have faith in the real-estate business? You’re worse off than I thought.”

“But we’re pricing it to sell.”

“How many offers have we had?”

“Well, none yet, but…”

“Exactly.” He leaned back, sipped coffee, and squinted at me with a grin. “You crazy wino, you’re serious about this, aren’t you?”

I nodded.

He shook his head and laughed. “Somehow I think you mean it this time. I hope you don’t blow out your knees on the first hill. Do you have any idea how much that garbage you’re taking is gonna weigh?“

“Should be the bike plus about a hundred pounds.”

His face crinkled into a balding vision of humor as he gazed into the distance. “Hey… I could use some of that stuff. I think I’ll wait at the bottom of the first good hill out in Muskingum County. As soon as you pedal by, I’ll follow you and pick up all the gadgets you’ve decided you don’t need after all. Let’s see… computer, CB, solar panels, binoculars…”

I laughed with him. “Well, after the shakedown cruise my legs should be in good shape.”

He sobered and leaned forward, propping his elbows on the $75 glass-topped table that hadn’t yet sold. “You know what happened last time you tried a long bike tour: you couldn’t walk for a week. I can tell you’re serious about this, you running dumb-ass, but you’ve got a few problems to solve in the next five months.” He raised his eyebrows and shoved the napkin toward me. “How do you plan to cover traveling expenses, assistant salary, monthly payments and emergencies — when you can only project two grand a month income?”

“I don’t know!” I was getting annoyed. “You want more coffee?”

Frank sighed and nodded. “You’re still just riding the rails, aren’t you?”

“In a way.” I refilled our cups and turned off the pot.

“What are your real reasons for this trip?”

“Well, it’s a chance to test the viability of the information society. I want to see if I can maintain an information-oriented professional practice while free from the confines of an office. Because I’ll have both freedom and security—“

“Yeah, yeah, stop quoting yourself — save that crap for newspaper reporters.”

I laughed. “Sorry. Um, the trip’s a combination of work and play. It ties together my motives: adventure, meeting people, doing something bizarre, high-tech toys, having plenty to write about, and so on.”

He shook his head in disgust. “Don’t forget chasin’ broads. You should have put that first.” Frank was devoutly Catholic in a freewheeling sort of way, and always made a point of giving me a hard time when I spoke of women.

“Well, there might be an element of that,” I admitted, wincing at the terminology.

“Right. An element of that. But you still left out the biggest reason.”

“What’s that?”

“You’re running away, that’s all the hell you’re doin’.”

“Not at all! This is just a creative way to restructure my life.”

“Aw, jeez, you should be a goddamn politician. Listen to yourself! You’re running away — you got your ass in debt, you’re sick of Ohio, and at thirty you still haven’t figured out what you want to do with your life. You’re too broke to move, so you’re gonna make a break for it on a funny-looking bicycle.”

“Well, philosophically, maybe.“

“You’re making a break for it. I didn’t say there was necessarily anything wrong with that, but it is what you’re doing. Isn’t it?”

“Maybe. But it has interesting possibilities.”

“Sure! It’s beautiful. I’m just trying to make you stop kidding yourself.” He raised his cup in toast. “I wanna see you pull it off!”

I was still defensive, and spoke with my arms crossed over my chest. “I intend to — on September 28! That’ll give me time to make it to the human-powered vehicle races in Indianapolis, then a shakedown through Louisville and Cincy before heading east…”

Frank’s grin, always just below the surface, broke forth. “OK, we gonna sit around dreaming all day, or you want to do something about getting your bike built?”

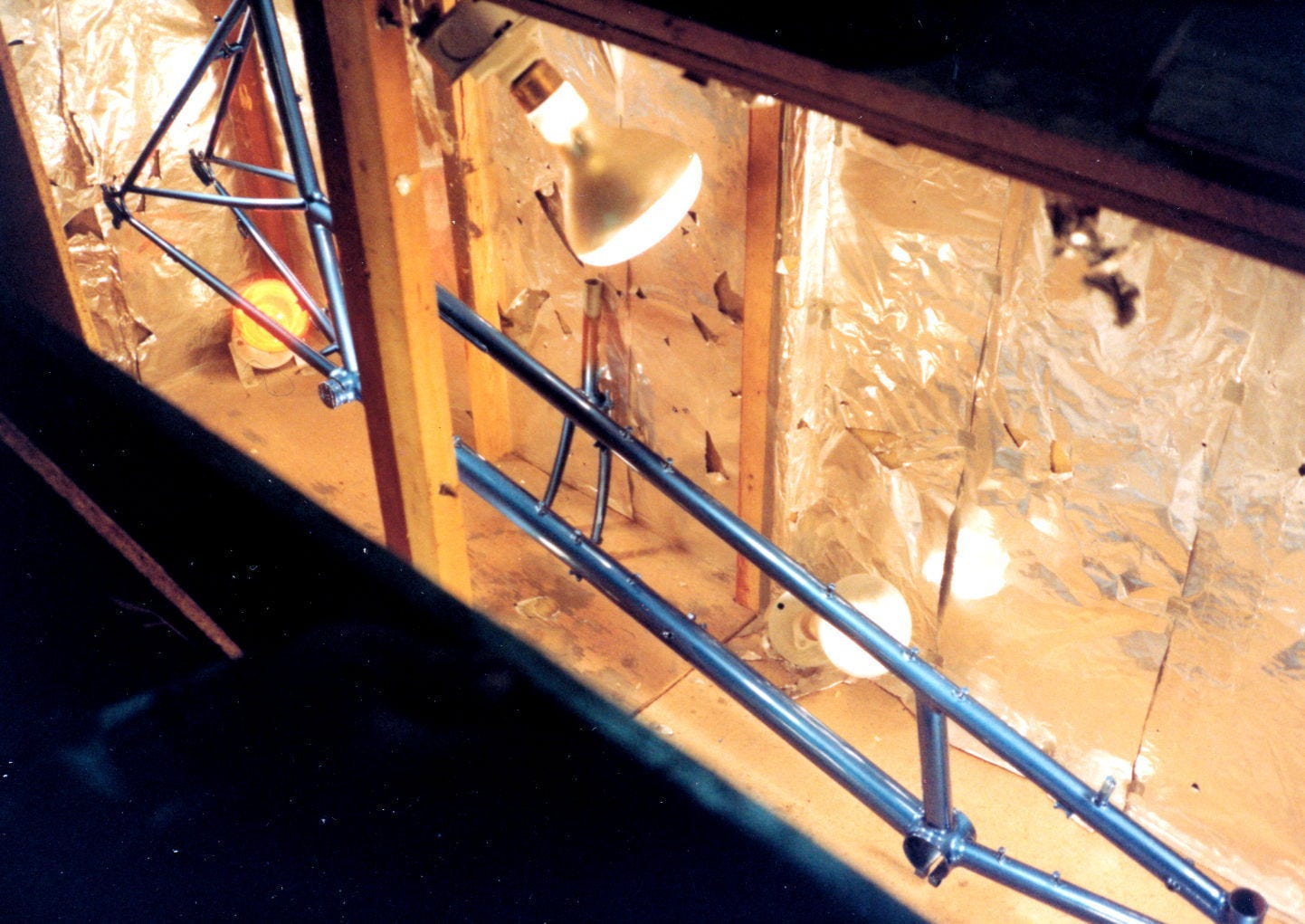

And so my basement, cleared by garage sales and trash projects, became a bike shop. As the weeks passed, a strange machine took shape beneath hastily installed fluorescents — conjured from discarded bicycle frames and scrounged components. In air acrid and hazy with brazing fumes, tongues loosened by beer, my friends and I built our first recumbent: the Junker. It was hideous and heavy — with a plywood seat onto which was duct-taped a yellowed foam pad. Once we got it to hang together we took it out for a test ride.

I strapped on my helmet and climbed aboard. A few motorists slowed to watch.

The Junker was clumsy, unlike the Avatar, but it worked. Part of the frame got in the way and limited gearing range, and the high handlebars were awkward — but still, it worked! We took turns bruising knees on the steering mechanism and whooping with delight, calling out speedometer readings until it was too dark to continue.

This was all very interesting, but it taught me that brazing and bicycle design are art forms, and I wouldn’t become proficient at them by September. The next day I went to visit Jack Trumbull of Franklin Frames.

Jack produced about 350 bicycle frames a year, and was well-known for his tandems. I had first approached him for newbie brazing advice, but after the Junker experience it became obvious that I should pay him to build the crazy thing. I laid out the plan over a Chinese dinner.

“You’re insane,” he said with a gruff twinkle.

The table before us was covered with food, photos, and drawings. We discussed frame geometry, fork rake, alloys, seat supports, steering linkages, solar panel mounting, and gearing… and by the time the food had cooled to an unappetizing cold paste we had the essence of a deal.

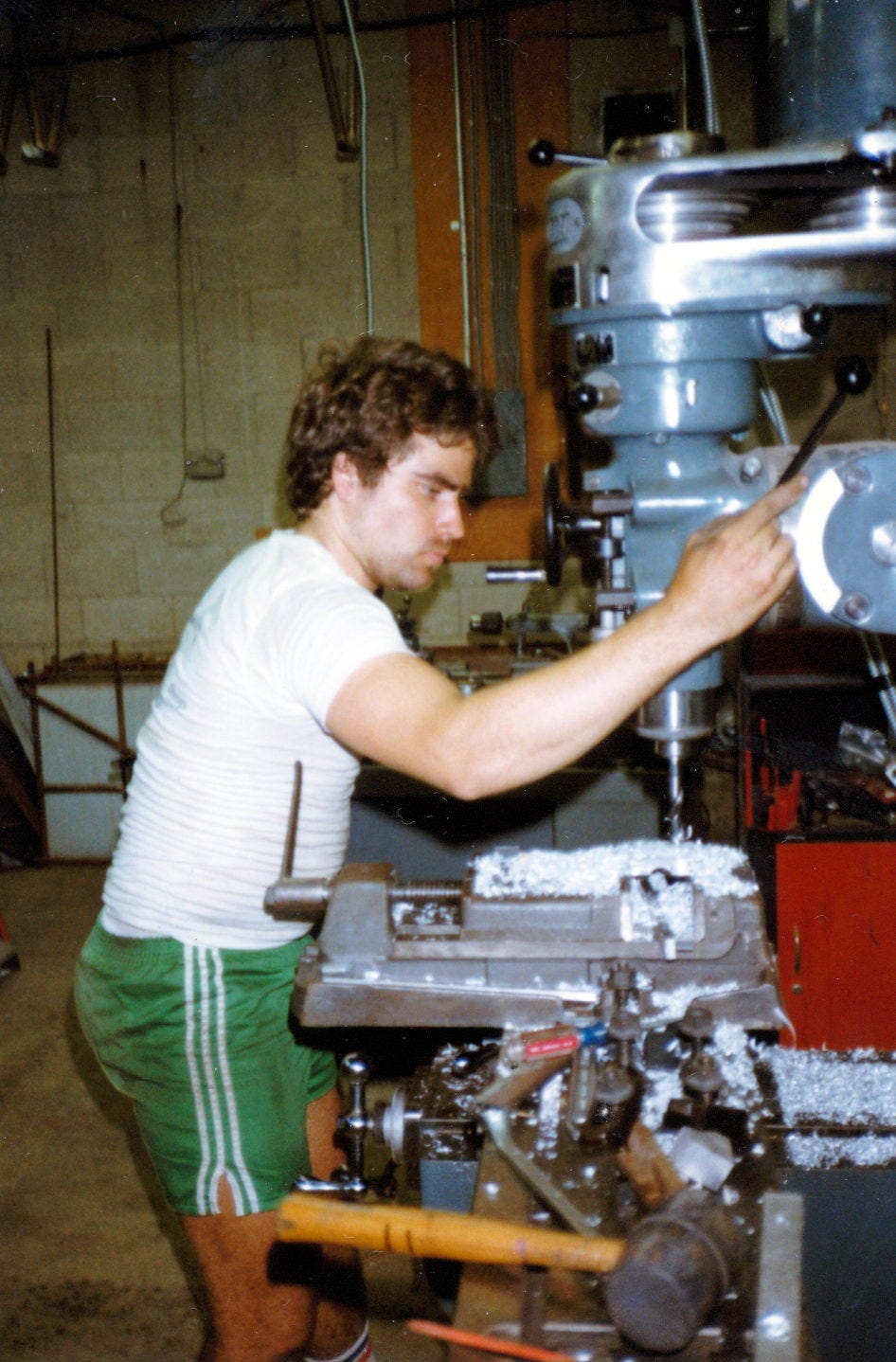

As the weeks passed and other parts of the system were coming together, I visited periodically — nervous about the deadline. He would peer at me from the shadows of his welding mask, scowl, call out an insult, and go back to work. His hands were steady, precise: from the clutter and filth of his workbenches arose exquisitely crafted creations of metal.

I dropped by the shop one mid-September day, expecting to see the completed frame with attached seat. Jack stood shirtless at the milling machine with his back to me, ankle-deep in aluminum tailings, sparkling bits of metal sweat-stuck to his hairy body like the bangles of industrial-punk couture. The radio was blasting and my frame leaned against the wall, seemingly forgotten. I called out a cheery hello to mask my impatience, not knowing that he had been up all night working on seat mounts.

He slowly turned and glared at me. In a voice low and menacing he snarled: “Get outta here — I wish you were dead!“

But it takes more than a finely balanced substrate of chrome-molybdenum steel to support a lifestyle of high-tech nomadics — more than the proceeds of a few garage sales to buy the five thousand calories a day required to fuel a human engine. While Jack was brazing away the summer afternoons and my engineer friends were helping with electronics, I was putting together a non-traditional company.

The office looked like any other — more casual, but equipped with the usual trappings. There were file cabinets, desks, baskets, a photocopier, swivel chairs, books, phones, and a computer system. But that’s where the similarity ended.

Running the office was Kacy, my universe interface (uniface) — and her daily commute involved trudging down the basement stairs in a housecoat, balancing infant Leah on one hip. Kacy’s job description was as odd as her workplace: Maintain the illusion of stability, electronically forward mail and messages, take care of all finances including cash transfers and bills, keep track of publicity, edit text, deal with publishers, and reassure my parents whenever fear of the unknown would drive them to call for news of their errant son. She worked alone, earning a flat percentage of my income and unlimited use of the company car.

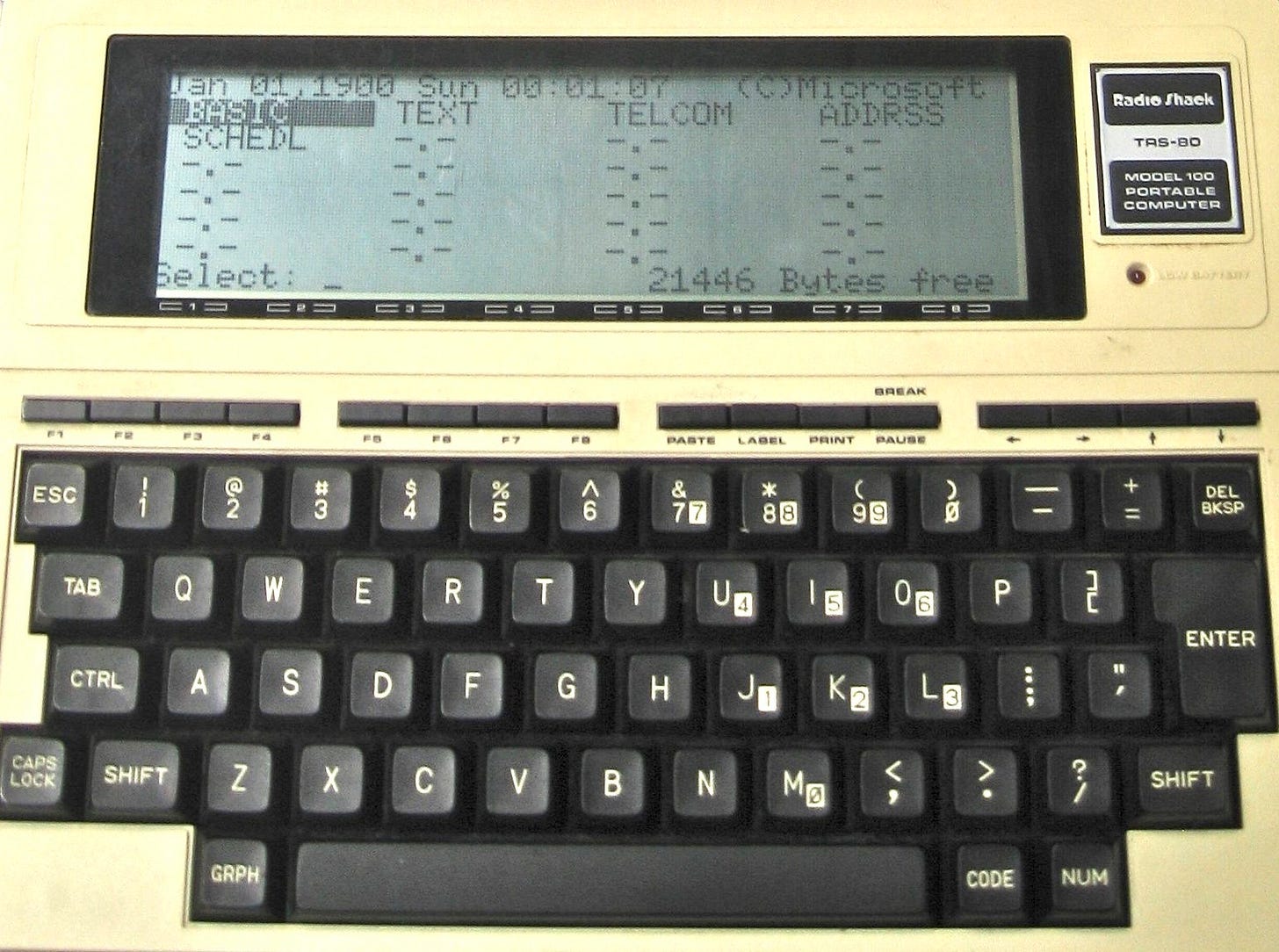

My four-pound portable computer was to be the remote-control console for all this — an electronic window through which I could view goings-on in Columbus and from which I would transmit the travel stories intended to keep us afloat. The Radio Shack Model 100 was a major breakthrough in 1983; not only did it contain essential software for text processing, BASIC programming, and file handling, but it could communicate with the rest of the world via built-in modem. That was the key.

The final, essential ingredient in my nomadic venture was the CompuServe network: from any telephone in the United States, pay or private, pushbutton or dial, I could sign on, get the mail, swap news with Kacy, move articles into our work area, and beg for another wire transfer of much-needed cash. And the network would turn out to be more than just a business connection — it was also to become the most stable component of my social life. With a user population at 80,000 and growing rapidly, CompuServe would quickly become my home town.

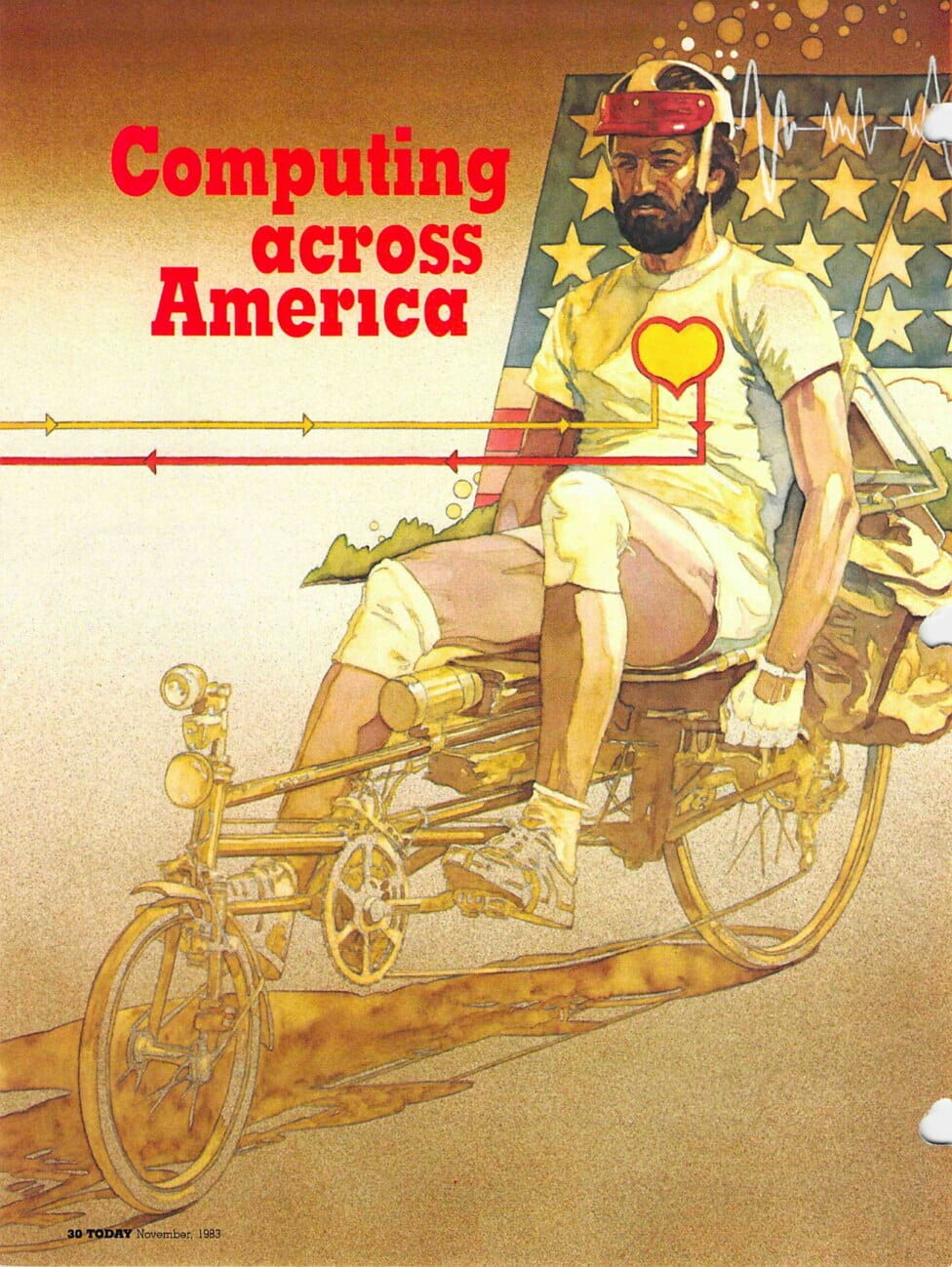

Setting up network housekeeping happened quickly — thanks to the user magazine Online Today. I had been freelancing for this glossy publication for well over a year, and it was the perfect place for a monthly column about my travels. Not only was there an obvious network tie-in, but every subscriber owns a computer and a CompuServe account. The “fan-mail” implications were staggering.

And it paid off immediately. The first Computing Across America article, announcing my upcoming odyssey, yielded nearly thirty pieces of electronic mail — most offering a hot shower and a place to stay. I began building the “hospitality database,” a sprawling file that would contain over three thousand invitations by journey’s end.

The pieces were falling into place.

One week to go! The bike emerged from Jack’s shop flawless and blue, hung with the glitter and sheen of European components, managing to look both sleek and gawky at the same time. I carried it into my living room with a sort of reverence. One week. I would begin living on this thing in one week. The night ahead would be one of installing accessories and working on the electronics package, but first I needed… something. A smile of understanding? I felt on the edge of madness.

Or panic.

“Elisse?”

“Hi!” My girlfriend’s familiar voice touched me through the phone and evoked memories of our year-long relationship. We hadn’t spent much time together recently — she had cast me adrift from her quiet devotion when it became obvious that the journey was not just a fantasy. “I’ll have to break your legs some night when you’re asleep,” she joked in early summer, hugging me. But now she was no longer playful; the emotional protection was well established.

“Hi there. Feel like getting together?”

“Right now?”

“Sure. I have something you might enjoy seeing.”

“I can just imagine. Does it have pedals and wheels?”

“How’d you guess?” The bike was an absurd choice of lure, given the circumstances.

“Oh, Steve, I suppose so…”

Within the hour we were on the waterbed, cuddling speechless, my cat nestled between our legs, tickling us with furry purrs just like the good old days. A week? Me a vagabond? Where would I be sleeping in one week? I drifted, trying not to think.

I was startled from nowhere by a tiny warm rivulet, coursing down my chest. Gently, I drew back and gazed into Sadness itself, framed in soft brown curls.

“Why?” she asked before I could whisper her name.

I sat up against the headboard of mirrors, then propped a pillow behind me and pulled her close. “I just want to have my cake and eat it too. That’s not too much to ask, is it?” I smiled reassuringly.

“That doesn’t have much to do with a bicycle trip.”

“However you look at it, ‘freedom versus security’ is the ultimate trade-off. If you want more freedom, you give up some security; if you want more security, you give up some freedom. You wanna run around? Fine — risk your marriage. You want a stable paycheck? Forget the flexibility of freelancing. You itching to travel? Give up home and hearth. The thing that’s so exciting about this odyssey is the fact that I should have both: a stable full-time business and a freewheeling adventure.”

“So I’m supposed to be happy for you?”

Later that night, I had a starker glimpse of her feelings. The “Computing Across America” phrase had recently been coined by Carole Gerber, writing about my journey for Online Today. Elisse read the article in silence and tossed it on the desk.

“Computing Across America, my ass,” she said. “It should be fucking across America.” She looked at me in absolute seriousness, silencing my laugh, then walked away.

The road was the Other Woman.

One week.

I've always wondered why you stuck with the same frame for every iteration of the bike but especially between Winnebiko 2 and BEHEMOTH. I guess I always thought it was just some off the rack recumbent frame not realising it had been custom built for the trip